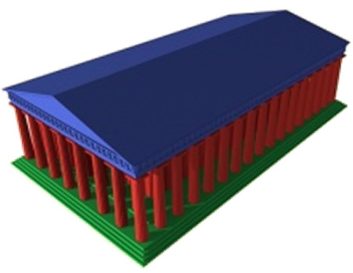

A ncient Greek temples followed a tripartite heightwise articulation having a base, a body and a crowning.

The base is the crepis that consists of three steps and the upper is called stylobate.

The body of the temple is the columns and the walls of the cella behind them.

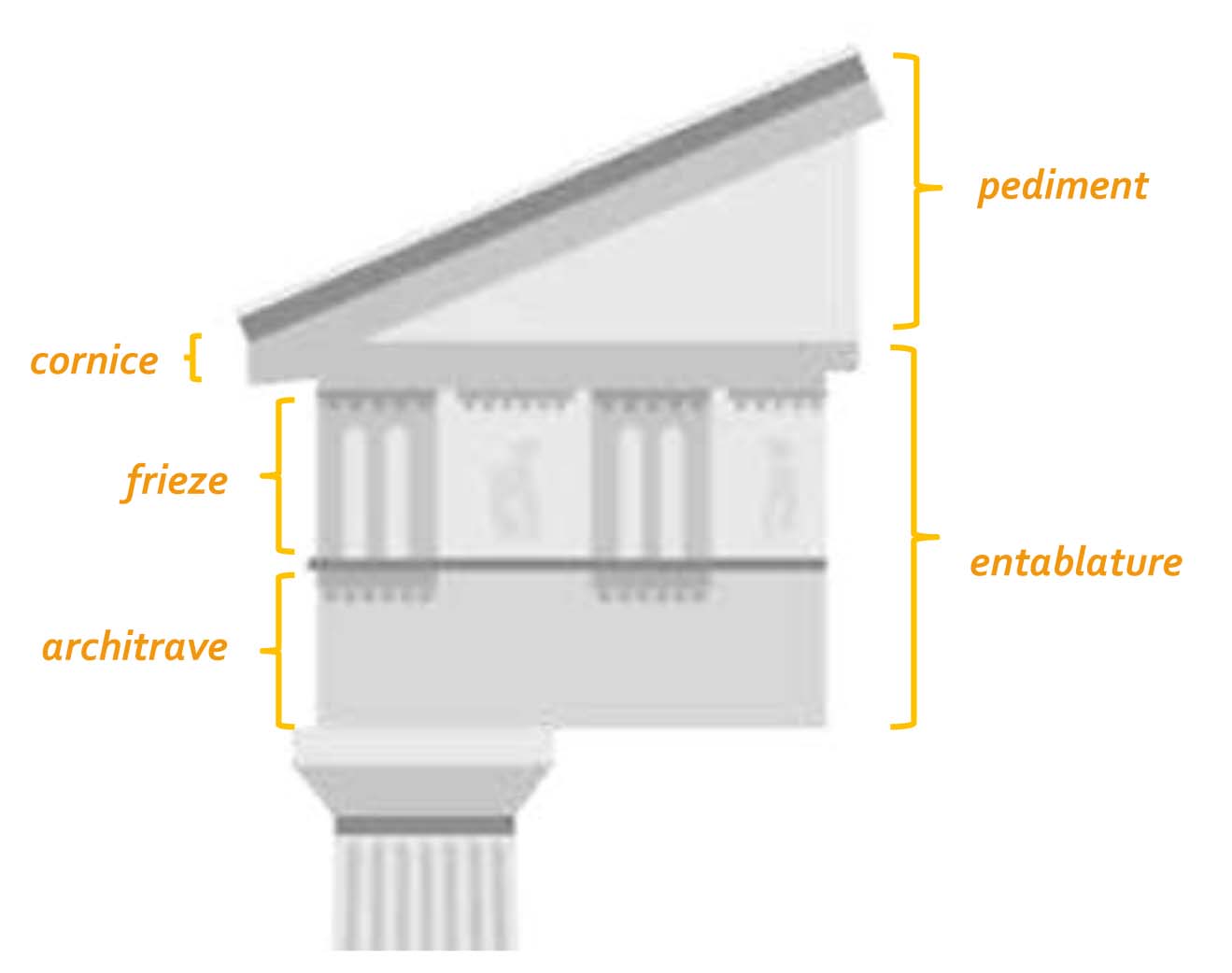

The crowning of the temple consists of the entablature and the pediments. The entablature consists of three distinct heightwise parts: the epistyle or architrave, the frieze (diazoma) and the cornice.

On the two narrow sides of the temple, in correspondence to the pitched roof and above the entablature, are the triangular pediments.

Three orders or styles can be distinguished in ancient Greek architecture: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian.

The order is not simply an ensemle of specific morphological features but a synthetic spirit which both contains and transcends them.The Doric and the Ionic order can be traced back to the Archaic period, while the third, the Corinthian, which is a variant of the Ionic, was created later, in the fourth century BC, and was mainly disseminated during the period of Roman rule. Doric temples have clarity and are severe and robust. Ionic temples are more elegant with richer decoration, variety and grace.

Ancient Greek architecture is essentially an architecture of beams on pillars; there are no arches, no cantilevers or other features that dynamically emphasize their height. The external columns and the overlying entablature are the principal bearers of the order.

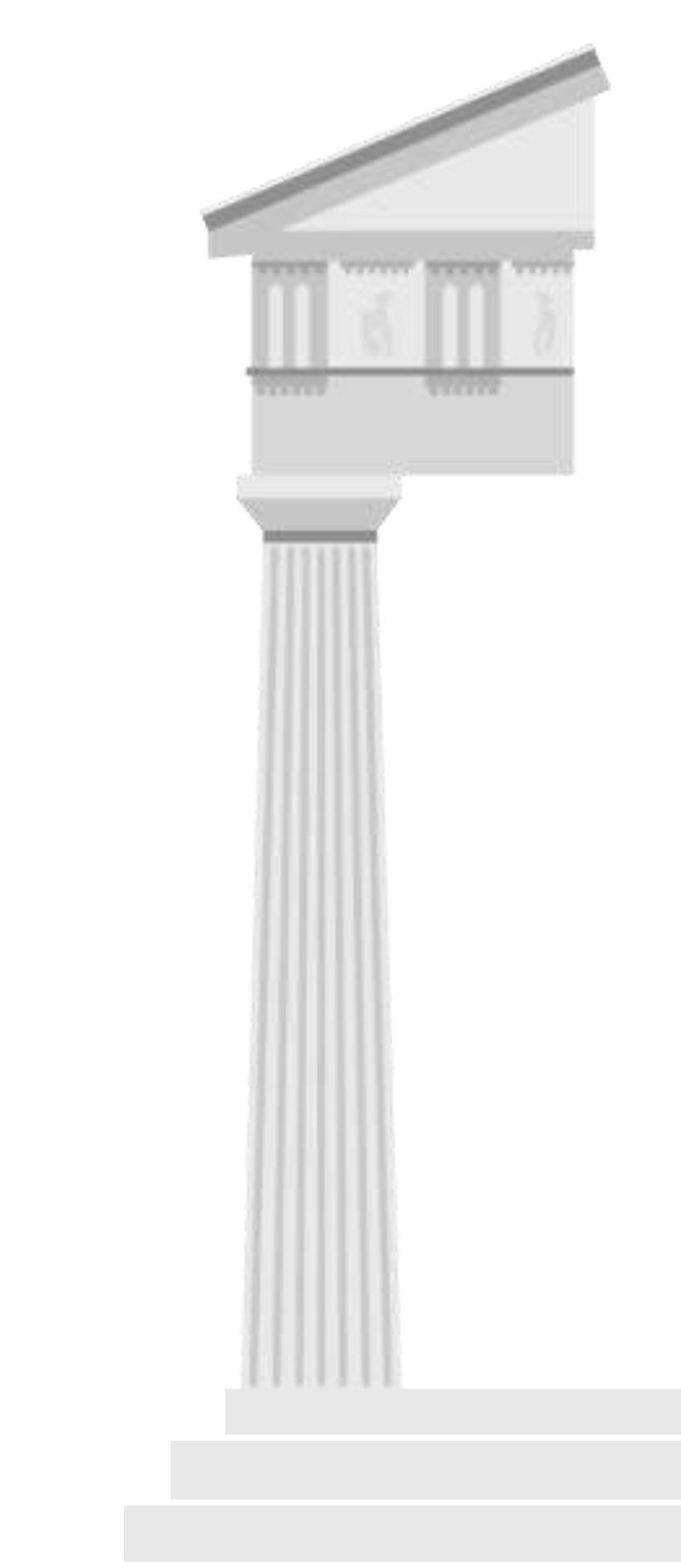

DORIC ORDER

T he features of the Doric order are already distinguishable in the very early temples, in clay and wood parts, that precede those constructed of stone. The order was created in Central Greece and the Peloponnese, diffused to the Greek colonies - particularely of Southern Italy and Sicily - and evolved continuously until its full maturity in the Athenian momuments of the second half of the fifth century BC.

Doric columns do not have a distinct base and are set directly on the uppermost step of the crepis, the stylobate. Their shaft has flutes and their diameter decreases appreciably upwards. It is usually comprised of drums (spondyloi) with horizontal joins between them.

The Doric capital is relatively plain, with an "echinus' of characteristic profile and an overlying square slab, the "abacus".

The architrave in the Doric order is plain too.

Its upper edge is decorated with a continuous "tainia" and with "regulae" at intervals, each of which bears six "guttae".

The Doric frieze or "diazoma" consists of "triglyphs" and "metopes". The triglyphs, which correspond to the columns and the axis of the intercolumniation, are of characteristic shape with two glyphs and two half-glyphs.

The metopes are virtually square plaques, which close the interstices between the tryglyphs and are decorated with relief representations on the richer monuments.

The cornice projects markedly above the frieze, so as to protect it and the architrave from rainwater. The shadow it casts over the underlying members increases its role in the crowning of the building.

In correspondence to each triglyph and each metope, the under surface of the cornice is decorated with rectangular plaques, the "mutules", each one of which bears three rows of six guttae.

Both pediments formed by the pitched roof, which covers the entire building, are bounded by raking cornices, without mutules. The pediments are closed behind by a wall, the tympanum. As a rule the pediment is decorated with sculptures, which stand on the horizontal cornice and are protected by the raking cornices. Above the latter runs the "sima", a special guttering that prevents the rainwater from the roof falling onto the pediment. At the three angles of the pediment are free-standing decorative elements, the "acroteria".

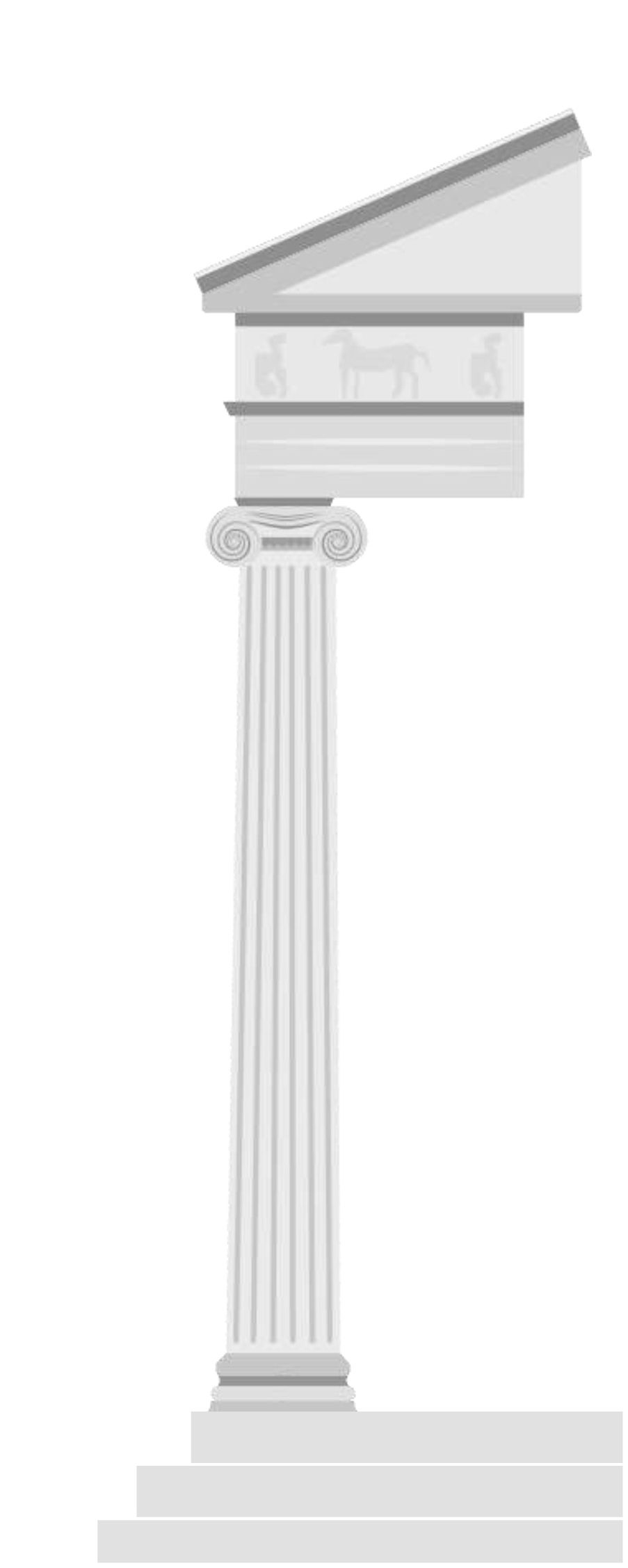

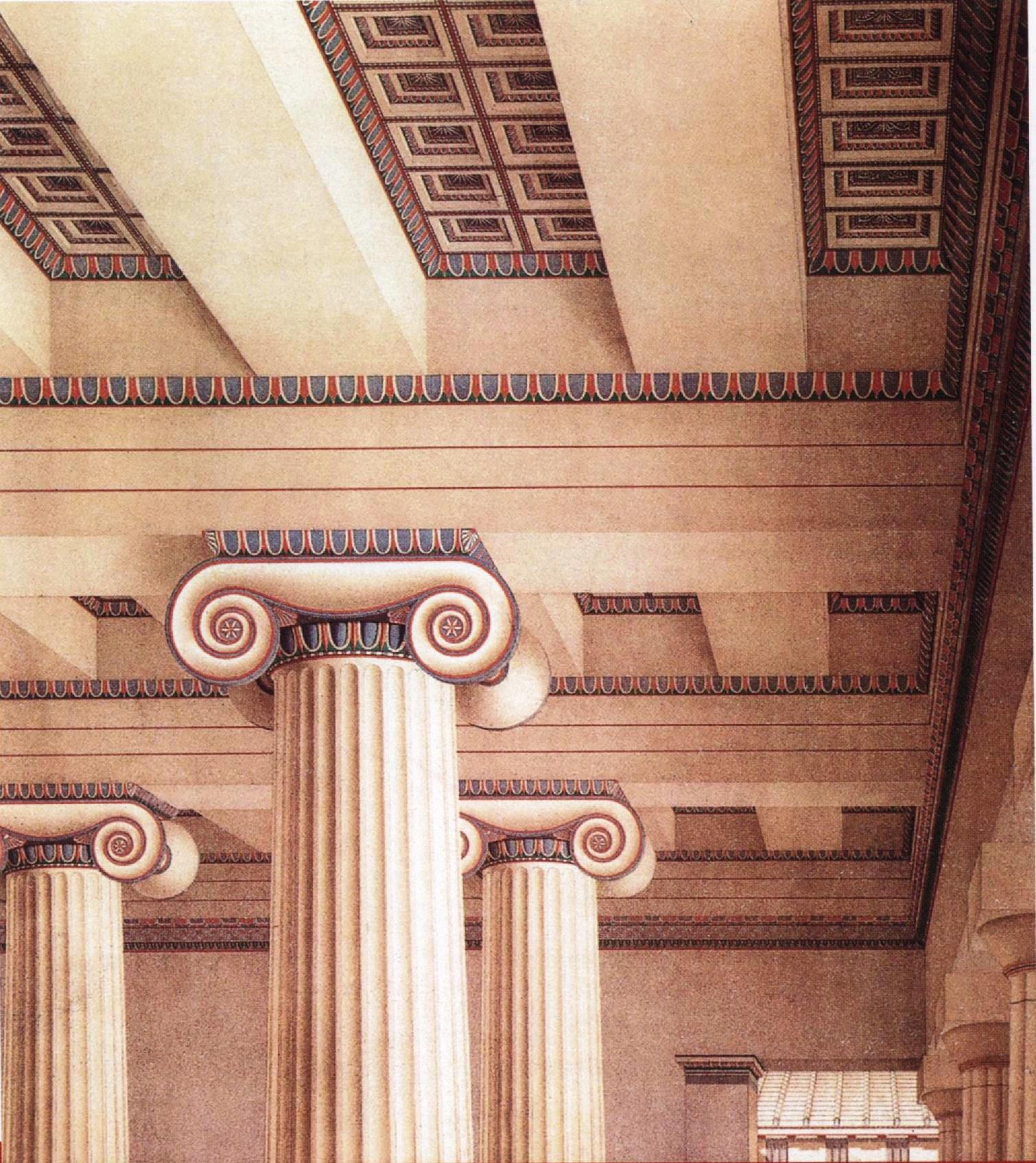

IONIC ORDER

T

he Ionic order also preserved some features of the timber constructions of the precursory buildings, but adopted many ornaments (volutes, rosettes, palmettes, continuous friezes) that were common in the decoration at rhe region of Asia Minor.

The Ionic order was indeed conceived and developed in Ionia, in the islands of the East Aegean and the Cyclades. In the Classical period it was adopted by Athenian architects, who created their most perfect examples of it on the Acropolis.

In the Ionic order the columns have bases.The column capital is of elongated shape. On its long sides, front and back, there are pairs of volutes, while on the narrow sides the so-called cushions or bolsters, reel-like surfaces. This composite member rests on an echinus which is adorned all round by Ionic cymatium while higher up is also an abacus, on which the architraves are bedded.

The face of the architraves consists as a rule of three regulae of equal height, crowned by a cymatium and immediately above runs the frieze, which here too is continuous and decorated with relief representations.

The cornice projects to protect the underlying members from rainwater, is undecorated and has a concave under-surface. The sima also extended above the cornice on the long sides and the rainwater collected in it was channelled to lion-head waterspouts set at intervals.

The pediments of monuments in the Ionic order were analogous to those of the Doric ones. Here too there was a sima above the raking cornices, but without waterspouts, while acroteria adorned the three angles.

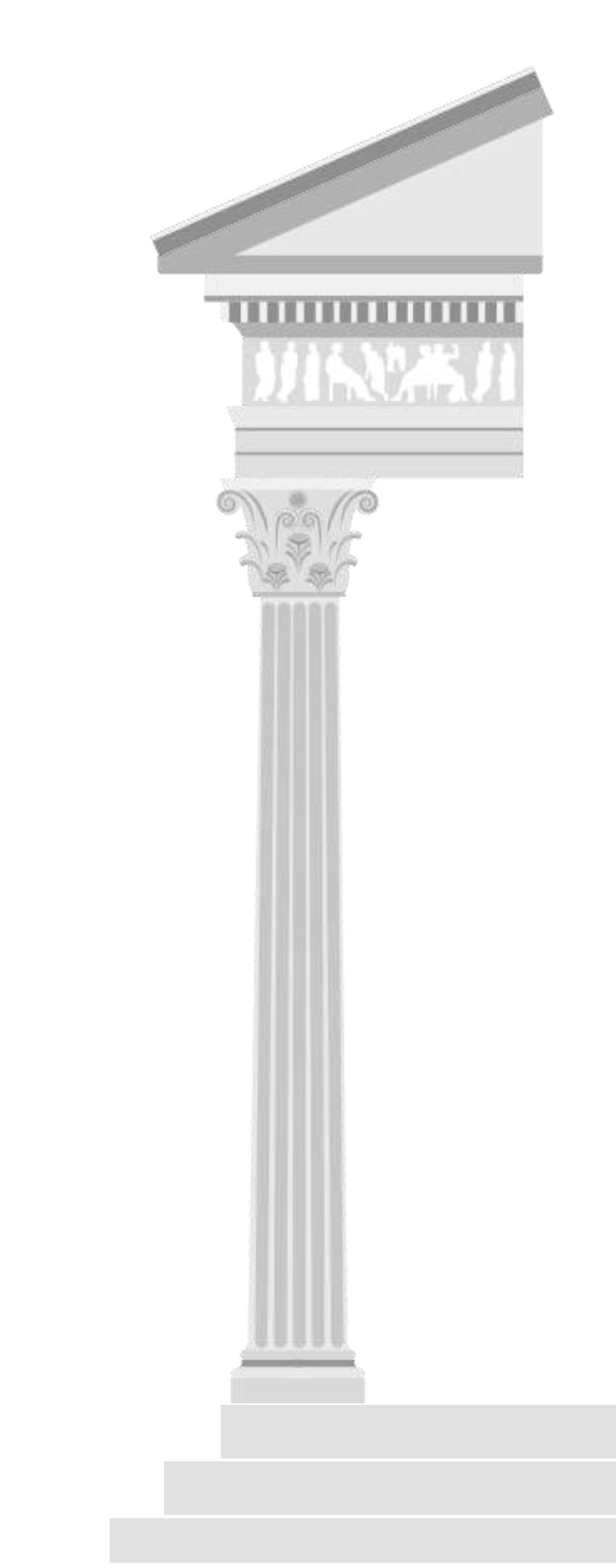

CORINTHIAN ORDER

T

he architectural member that differentiates the Corinthian order from the Ionic is the column capital, which is embellished with acanthus leaves in two successive rows, and pairs of volutes that meet in twos at its four corners.

It is generally believed that this elaborate type of column capital was created by the sculptor and bronze-caster Callimachos, and that the earliest application of it in architecture was by Ictinos in the temple of Apollo Epicourios at Bassae, in Arcadia.

Morphological analysis of the Corinthian column capital shoes that the overlying entablature was not supported by the leaves and volutes but by its stable nucleus, the "calathos".

In the Corinthian order, as in the Ionic, application of the morphological canon was not particularly strict, resulting in the creation of different variations of colum capitals by the architects. Some of the earliest and loveliest examples are to be seen on the choregic monument of Lysicrates in Athens and in the Tholos at Epidaurus.

REFINEMENTS

T he remarkable and impressive quality of ancient Greek temples is expressed in the famous visual refinements, the imperceptible deviation from the geometric forms, the purpose of which was to endow the inanimate buildings with organic vitality.

In the Parthenon the visual refinements are present in their most consummate form. All the lines of the crepis are very slightly convex and not exactly straight. The columns incline very slightly inwards, towards the cella, and their shafts have a barely perceptible swelling, the entasis, which reaches its maximum at 2/5 of their height. The corner columns of each side are very slightly thicker than the rest and the distance between them and the adjacent ones is slightly less than the normal intercolumniations. The entablature has an analogous curvature to the crepis.

The experimentation with this system of almost invisible refinements evidently commenced in the Early Archaic period.

CEILINGS

I

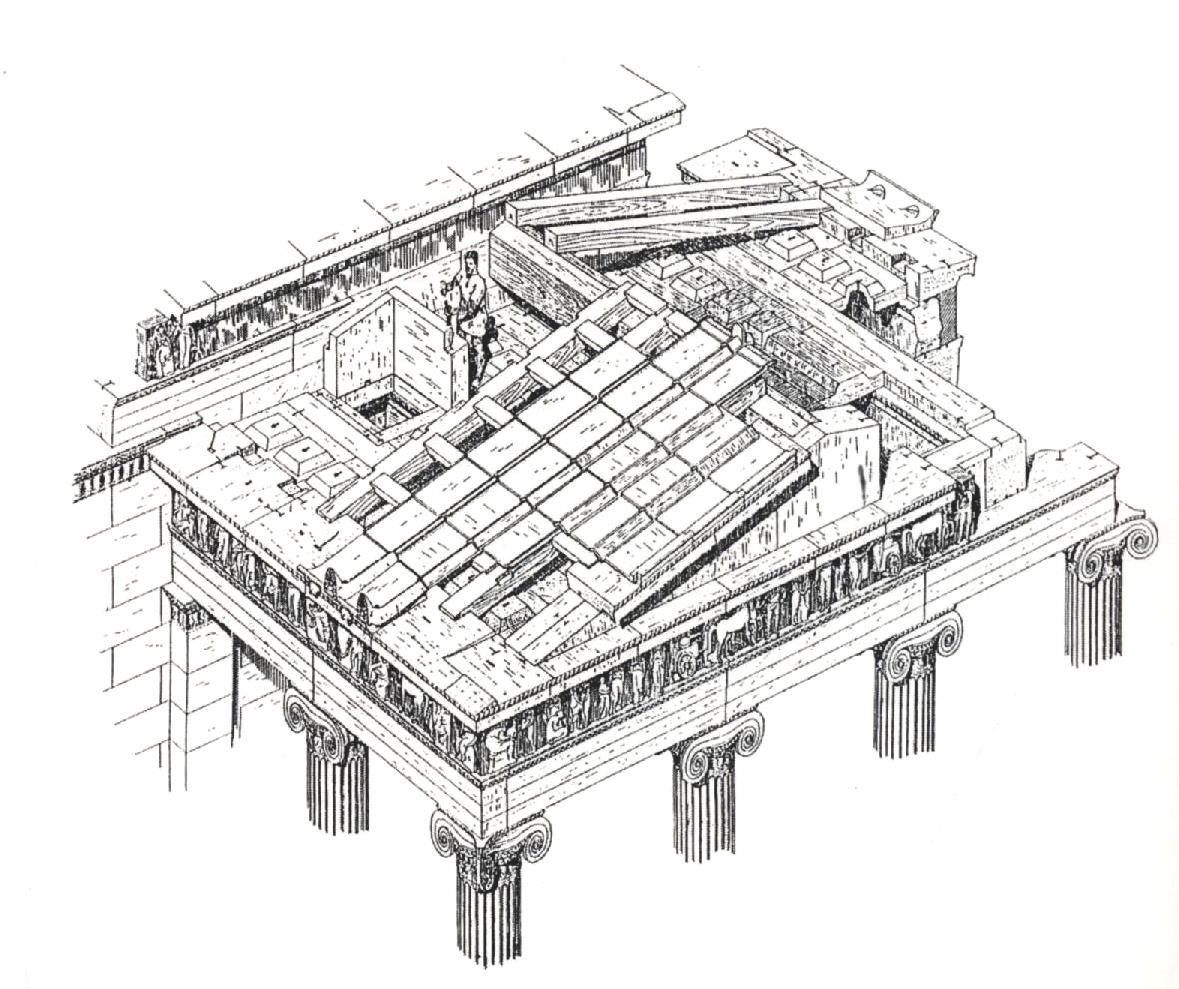

n the ancient Greek temples, independently of their order, the "peristasis" around the cella was covered by marble ceilings that were formed of oblong plaques on the under surface of which were square recesses, the "coffers".

When the openings were large, as in the "Theseion" and the Parthenon, transverse marble beams underpinned the coffered plaques.

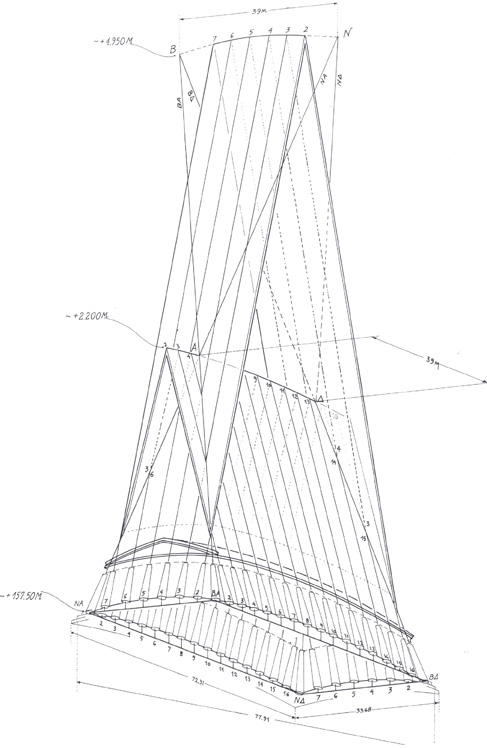

ROOFS

O n top of the cella and the marble ceilings of the peristasis, a pitched roof was constructed. This was the only part of the ancient temple that was made of wood and therefore all that has survived today are the mortises in the marble members for the horizontal beams of the timbers. The large rafters that formed the roof rested on the walls of the cella, on the columns - interior and exterior - and on wooden orthostats that stood on the axis of the cella, above the architraves of the internal colonnade.

The roof was covered with tiles, which in opulent and distinguished edifices, such as those on the Athenian Acropolis, were also of marble. Usually, however, the tiles were of terracotta and, unlike today’s roof tiles, were not all the same; they were distinguished into covering tiles (imbrices) and narrow rain tiles (tegulae) which covered the interstices between these. The rain tiles at the edges of roofs, that is above the cornices, were decorated with palmettes and called antefixes.